Scientists in the United Kingdom have, for the first time, “thrown some light” on the unsurpassed speed and agility of the cheetah, using a special solar-powered collar to track its movements. The knowledge will be used not only by naturalists, but by automation experts, who are working on the development of CHEETAH, the world’s fastest legged robot.

The cheetah—a big cat found in Africa and the Middle East—can sprint at 65 miles per hour, making it the fastest land animal by far. Elite polo horses are sluggish by comparison, moving at most at a mere 40 miles per hour. Cheetahs also are extremely nimble—enabling them to catch even the most adroit prey. But what is it about the cheetah that enables it to do this? Until very recently, scientists didn’t know.

While cats in captivity have been tested chasing a tethered lure, cheetahs had never been assessed under natural conditions. A team led by Professor Alan Wilson of the Royal Veterinary College’s Structure & Motion Laboratory near London worked with the Botswana Predator Conservation Trust in the Okavango Delta region of Northern Botswana to measure the performance of cheetah hunting in the wild.

Solar Collars

The scientists fitted a three female and two male wild cheetahs with collars equipped with a special high-accuracy global positioning system (GPS) to pinpoint the cats’ location and speed; as well as acceleration sensors, miniature gyroscopes, a compass and a tiny low-power computer.

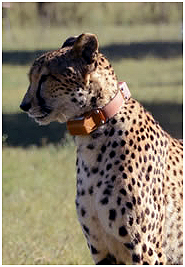

A cheetah wearing a collar looks for prey in northern Botswana.

In addition to rechargeable and non-rechargeable batteries, a set of high-efficiency solar cells on each collar typically provides about a quarter of the collar’s power requirements, greatly extending the operating life of the collar before battery exhaustion

Over a period of 17 months, the sensors detected the cheetahs’ exact footfall pattern24/7, documenting how many strides the big cats took and when each paw hit the ground. The collars monitored exactly where each cheetah was and what it was doing — resting, walking, or most importantly, hunting — and only collected detailed information when the cheetahs were moving quickly (logging data up to 300 times per second during 367 documented runs). The collar data were stored for later download via an integral radio link.

The team also used a high-resolution, high-speed video camera on a mount that automatically pointed at a GPS-derived location identified by the collars and communicated via the radio link. Because the cameras and collars were precisely synchronized, the team was able to examine the collar data and video footage of the hunt step by step—including the terrain, obstacles and interaction with the prey.

From Results to Robots

The results, from the team at the Royal Veterinary College’s Structure & Motion Laboratory, have now been published in the June 13 edition of Nature and are also featured on the journal’s cover.

Data revealed that wild cheetah runs started with a period of acceleration, either from stationary or slow movement (presumably, stalking) up to high speed. The cheetahs then decelerated and maneuvered before prey capture. About one-third of runs involved more than one period of sustained acceleration. In successful hunts, there was often a burst of accelerometer data after the speed returned to zero, interpreted as the cheetah subduing the prey— in this case mainly Impala, which made up 75 percent of their diet.

The average run distance was 190 yards. The longest runs recorded by each cheetah ranged from 445 yards to 611 yards and the mean run frequency was 1.3 times per day. The greatest acceleration and deceleration values were almost double values published for polo horses and exceeded the accelerations reported for greyhounds at the start of a race. The acceleration power for the cheetahs was four times higher than that achieved by Usain Bolt during his world record 100- meter run, about double that for racing greyhounds and more than three times higher than polo horses in competition.

In the end, the data will be used, not only by biologists, but by robotics experts. Robot designers look to nature for inspiration for the design of dynamic, free-ranging and legged robots. One company in particular, Boston Dynamics, is developing CHEETAH, the world’s fastest legged robot.

Alan Wilson’s role in the CHEETAH project is to discover and translate the mechanics of cheetah locomotion into engineering principles that can be used by robot designers. By understanding the basic principles of how animals run, remain stable and use their muscles it should be possible to make legged robots that are faster, more capable on varied terrain and more economical.

Edited by Rich Steeves